The Lightning Conductor - December 3

In which Brown familiarizes himself with the "dragon" and its passengers, and the tour begins in earnest, despite interruption by a rival and a fire...

Compiler’s Note: Buckle in for a long installment today! Today, I present three letters, one from Jack and two from Molly. The first of Molly’s letters is dated “November Something-Or-Other” while the second is dated December 3 and states that she has not written in three days. While this would suggest that her first letter dates to November 30, it appears to take place after the events of Jack’s letter of December 3, so I have elected to present them all together in publication order.

FROM JACK WINSTON TO LORD LANE

Hotel de Londres, Amboise,

December 3.

My dear Montie,

The plot thickens. She is Superb. But things are happening which I didn't foresee, and which I don't like. I have to suppress a Worm, and suppressed he shall be. I am writing this letter to you in my bedroom. It is three in the morning, and a lovely night - more like spring than winter. Through my wide-open window the only sound that comes in is the lapping of the lazy Loire against the piers of the great stone bridge. I have not been to bed; I shall not go to bed, for I have something to do when dawn begins. Though I have worked hard to-day, I am not tired; I am too excited for fatigue. But I must give you a sketch of what has happened during the last few days. It is a comfort and a pleasure to me to be able to unburden myself to your sympathetic heart. You will read what I write with patience, I know, and with interest, I hope. That you will often smile, I am sure.

I sent you a line from Orleans, telling you that I had got myself engaged as chauffeur to Miss Molly Randolph at Suresnes. Well, the garage man and I managed to fit the new crank into my lovely employer's abominable car, and about three or four in the afternoon we were ready to take the road. As I tucked the rug round the ladies Miss Randolph threw me an appealing look. "My aunt," she said, "declares that it is quite useless to go on, as she is sure we shall never get anywhere. But it is a good car, isn't it, Brown, and we shall get to Tours, shan't we?" "It's a great car, miss," I said quite truthfully and very heartily. "With this car I'd guarantee to take you comfortably all round Europe." Heaven knows that this boast was the child of hope rather than experience; but it would have been too maddening to have the whole thing knocked on the head at the beginning by the fears of a timorous elderly lady. "You hear, Aunt Mary, what Brown says," said the girl, with the air of one who brings an argument to a close, and I hastened to start the car.

By Jove! The compression was strong! I wasn't prepared for it after the simple twist of the hand, which is all that is necessary to start the Napier, and the recoil of the starting-handle nearly broke my wrist. But I got the engine going with the second try, jumped to my place in front of the ladies (you understand that it is a phaeton-seated car), and started very gingerly up the hill. Though I was once accustomed to a belt-driven Benz (you remember my little 3½ horse-power "halfpenny Benz," as I came to call it), that had the ordinary fast and loose pulleys, while this German monstrosity is driven by a jockey-pulley, an appliance fiendishly contrived, as it seemed to me, especially for breaking belts quickly. The car too is steered by a tiller worked with the left hand, and there are so many different levers to manipulate that to drive the thing properly one ought to be a modern Briareus.

I must say, though, that the thing has power. It bumbled in excellent style on the second speed up the long hill of Suresnes; but when we got to the level and changed speeds, I put the jockey on a trifle too quickly, and snick! went the belt. I was awfully anxious that my new mistress shouldn't think me a duffer, that she shouldn't lose confidence in her car and me, and determine to bring her tour to an abrupt end; so as soon as I felt the snap I turned round saying it was only a broken belt that could be mended in no time. She smiled delightfully. "How nice of you to take it so well!" she said." Rattray seemed to think that when a belt broke the end of the world had come."

Now to mend a belt seems the easiest thing going, and so it is when you merely have to hammer a fastening through it and turn the ends over. But in this car you have to make the joint with coils of twisted wire. Simple as it is to do in a workshop, this belt-mending is a most irritating affair by the roadside, and when done I found by subsequent experiences that the wires wear through and tear out after less than a hundred miles.

On this first day, not having the hang of the job, I found it disgustingly tedious. To begin with, to get at the pulleys I had to open the back of the car, and that meant lifting down all the carefully strapped luggage and depositing it by the roadside. Then the wire and tools were either in a cupboard under the floor of the car or in a box under the ladies' seats, which meant disturbing them every time one wanted anything. How different to my beautifully planned Napier, where every part is easily accessible!

The mending of that third speed-belt took me half an hour, and after that we made some progress; but dusk coming on, I suggested to the ladies that as there was very little fun in travelling in the dark, I thought they had better stay the night at Versailles, going on to Orleans the next day. They agreed.

I had thought out plans for my own comfort. I knew that at some of the smaller country inns there would be no rooms for servants, and that I should have to eat with the ladies, which suited me exactly. In the larger towns, rather than mess with the couriers, valets, and maids, I should simply instal my employers in one hotel, then quietly go off myself to another. That is what I did at Versailles. I saw the ladies into the best hotel in the town, drove the car into the stable-yard, and went out to watch for Almond. He had followed us warily and had stopped the Napier in a side street two hundred yards away. I joined him, and we drove to a quiet hotel about a quarter of a mile from Miss Randolph's. I had my luggage taken in, bathed, changed, and dined like a prince, instructing Almond to be up at six next morning and thoroughly clean and oil the German car, making a lot of new fastenings in spare belts. Later in the day he is to follow us to Orleans with the Napier. Thus I live the double life - by day the leather-clad chauffeur; by night the English gentleman travelling on his own car. The plans seem well laid; I cover my tracks carefully; I don't see how detection can come.

With a good deal of inward fear and trembling I drove the car at eight the next morning to the door of Miss Randolph's hotel. She and her masked and goggled aunt appeared at once, and in five minutes the luggage was strapped on behind.

"Now please understand," said the girl, with a twinkle of merriment, in her eyes, "that this is to be a pilgrimage, not a meteor flight. Even if this car's capable of racing, which I guess it isn't, I don't want to race. I just want to glide; I want to see everything; to drink in impressions every instant."

This suited me exactly, for it gave me a chance of humouring and studying the uncouth thing that I was called upon to drive. I had come out to Versailles to avoid the direct route to Orleans by Etampes, which is pavé nearly all the way, and practically impassable for automobiles. From Versailles there is a good route by Dourdan and Angerville, which, if not picturesque, at least passes through agreeable, richly cultivated country. The road is exceedingly accidentée on leaving Versailles, and I drove with great care down the dangerous descent to Châteaufort, and also down the hill at St. Rémy, which leads to the valley of the Yvette. Till beyond Dourdan the road is one long switchback, and it is but fair to record that the solid German car climbed the hills with a kind of lumbering sturdiness much to its credit. At Dourdan we lunched, and soon after entered on the long, level road to Orleans. The car travelled well - for it, and the day's record of sixty-seven miles was only three breakages of belts. To my relief and surprise we actually got to Orleans in time for dinner. I was a proud man when I drove my employers into the old-fashioned courtyard of the d'Orleans. Almond, I knew, was at the St. Aignan with the Napier, and there I presently joined him, to hear that he had done the total run from Versailles, with an hour's stop for lunch, in under the four hours, the car running splendidly all the way. Almond does not at all understand why he is left alone, and why I have gone off to drive two ladies in an out-of-date German car which any self-respecting automobilist would be ashamed to be seen on in France. He looks at me queerly, and would like to ask questions; but being a good servant as well as a good mechanic, he doesn't, and kindly puts up with his master's whims.

My orders were to be ready for the ladies at ten the next morning, and when punctually to the moment I drove the car into the courtyard, I found them waiting for me. Miss Randolph volunteered the news that she and her aunt had been round the town in a cab to see the sites connected with the Maid, but that she had found it very difficult to picture things as they were, so modernised is the town.

The morning we left Orleans was exquisite. The car went well; the magnificent Loire was brimming from bank to bank, and not meandering among disfiguring sand-banks, as it does later in the year; the wide, green landscape shone through a glitter of sunshine; and here and there in the blue sky floated a mass of tumbled white cloud. Our little party at first was silent. I think the beauty of the scene influenced us all, even Aunt Mary; and the thrumming of the motor formed a monotonous undercurrent to our thoughts.

As I've told you, the German horror is phaeton-seated, and for me in front to talk comfortably to any lady behind is not easy. In driving, one can't take one's attention much off the road, so Miss Molly has to lean forward and shout over my shoulder. A curious and delightful kind of understanding is growing up between us. You know that the history of this part of France is fairly familiar to me, and I've already done the castles twice before. What I've forgotten, I've studied up in the evenings, so as to be indispensable to Miss Randolph. At first she spoke to me very little, only a kind word now and then such as one throws to a servant; but I could hear much of what she said to her aunt, and her comments on things in general were sprightly and original. She had evidently read a good deal, looked at things freshly, and brought to bear on the old Court history of France her own quaint point of view. Her enthusiasm was ever ready-bubbling, but never gushing, and I eagerly kept an ear to the windward not to miss the murmur of the geographical and historical fountain behind my back.

"Aunt Mary," on the contrary, has a vague and ordinary mind, being more interested in what she is going to have for luncheon than in what she is going to see. The girl, therefore, is rather thrown back upon herself. I burned to join in the talk, yet I dared not step out of the character I had assumed. As it turned out, fortune was waiting to befriend me.

We were bowling along through Meung, when I suddenly spied on the other side of the river the square and heavy mass of Notre Dame de Cléry, and almost without thinking, I pointed it out to Miss Randolph. "There is Cléry," I said, "where Louis the Eleventh is buried. You remember, in Quentin Durward? The church is worth seeing. It's almost a pity we didn't go that side of the river." Then I stopped, rather confused, fearing I had given myself away. There was a moment's astonished silence, and I was afraid Miss Randolph would see the back of my neck getting red.

"Why, Brown!" she cried, leaning forward over my shoulder, "you know these things; you've read history?"

"Oh yes, miss," I said. "I've read a bit here and there, such books as I could get hold of. I was always interested in history and architecture, and that sort of thing. Besides," I went on hastily, "I've travelled this road before with a gentleman who knows a good deal about this part of France."

I don't think that was disingenuous, was it? - for I hope I've a right to call myself "a gentleman."

"How lucky for us!" cried Miss Randolph, and I heard her congratulating herself to her aunt, because they had got hold of a cicerone and chauffeur in one. After that she began to talk to me a good deal, and now she seems to show a kind of wondering interest in testing the amount of my knowledge, which I take care to clothe in common words and not to show too much. You must admit the situation grows in piquancy.

At Mer we crossed the Loire by the suspension bridge and ran the eight miles to Chambord, meaning to lunch there, and go on to Blois after seeing the Château. It was a grand performance for the car to run nearly three hours without accident. While luncheon was being prepared I filled up the water-tanks (even this simple task involved lifting all the luggage off the car), washed with some invaluable Hudson's soap, which I had brought from my own car, and made myself smart for déjeuner. The eating business will, I can see, be one of my chief difficulties. At Chambord, for instance, in the small hotel, there is, of course, no special room for servants. As I have no fondness for eating in stuffy kitchens when it can be avoided, I wandered sedately into the salle à manger, where Miss Randolph and her aunt were already seated, and took a place at the further end of the same long table (we were the only people in the room). Aunt Mary looked for an instant a little discomposed at the idea of lunching with her niece's hired mechanic, but Miss Randolph, noticing this - she sees everything - shot me a welcoming smile. Then the paying difficulty is an odious one. Of course, at the end of the meal my bill goes to her, and she pays for me: "Mécanicien, déjeuner--" so much. Picture it! Of course, I can't protest, as this is the custom; but I am keeping a strict account of all her expenses on my account, and one day shall square our accounts somehow - I don't at present see how. I have formed the idea that by-and-by I may offer to act also as courier, relieving her of the bother of making payments, and so on. If I can work that, I'll deduct my own lot and pay it myself, the chances being that as she is careless about money she won't notice that I've done so, only thinking, perhaps, that I am a clever chap to run things so cheaply.

There's another thing which gives me the "wombles," as those delightful Miss Bryants used to call the feeling they had when they were looking forward to any event with a mixture of excitement, fear, and embarrassment.

Well, I have the "wombles" when I think of the moment, near at hand, when Miss Randolph will hand me my weekly wage, which I have put at the modest figure of fifty francs a week; but I am getting away from the déjeuner at Chambord.

We had just finished the crôute au pot, when there came a whirr! outside, upon which Miss Randolph looked questioningly at me. "A little Pieper," I said. "How wonderful!" she exclaimed. "Can you really tell different makes of cars just by their sound?" "Anyone can do that," I informed her, "with practice; you will yourself by the time you get to the end of this journey. Each car has its characteristic note. The De Dion has a kind of screaming whirr; the Benz a pulsing throb; the Panhard a thrumming; a tricycle a noise like a miniature Maxim."

The driver of the Pieper came in. His get-up was the last outrageous word of automobilism - leather cap with ear-flaps, goggles and mask, a ridiculously shaggy coat of fur, and long boots of skin up to his thighs - a suitable costume for an Arctic explorer, but mighty fantastic in a mild French winter. You know these posing French automobilists. At sight of a beautiful girl, he made haste to take off his hat and goggles, revealing himself as a good-looking fellow with abnormally long eyelashes, which I somehow resented. He preened himself like a bird, twisted up the ends of his black moustache, and prepared for conquest. Catching Miss Randolph's eye, he smiled; she answered with that delightful American frankness which the Italian and the Frenchman misconstrue, and in a moment they were talking motor-car as hard as they could go. The poor chauffeur was ignored.

It undermines one's sense of self-importance to find how quickly one can be unclassed. I tasted at this moment the mortification of service. Once in an hotel at Biarritz I gave to the valet de chambre a hat and a couple of coats that I didn't want any more. They were in good condition, and he was overwhelmed with the value of the gift. "Monsieur is too kind," the fellow said; "such clothes are too good for me. They are all right for you, but for nous autres!" - the "others," who neither expect the good things of life nor envy those who have them. The expression implies the belief that the world is divided into two parts - the ones and the other ones.

Now, as I heard my sweet and clever little lady babbling automobilism with all the wisdom of an amateur of six weeks, I felt that I was indeed one of the Others. Though the Frenchman was to me a manifest Worm (in that he was supercilious, puffed up with conceit, taking it for granted that women should fall down and worship him) and a ridiculous braggart, I had to see her receive his open admiration with equanimity and listen to his stories with credulity, my business being to eat in silence and "thank Heaven" (though not "fasting") that I was allowed in the presence of my betters. Still, I would have gone through more than that to be near her, to hear her talk, and see her smile, for frankly this girl begins to interest me as no other woman has.

"Ah, how I have travelled to-day!" the Frenchman said, throwing his hands wide apart. "I left Paris this morning, to-morrow I shall be in Biarritz. To-day I have killed a dog and three hens. On the front of my car just now I found the bones and feathers of some birds, which miscalculated their distance and could not get away in time." Miss Randolph gave a little cry, translating for her aunt, who has no French.

"Shocking!" ejaculated Aunt Mary. "A regular juggernaut."

"Your car does not go as fast as that, mademoiselle?" the Frenchman went on. "A little heavy, I should think; a slow hill-climber?"

"On the contrary," Miss Randolph fired up. "Though my car has-er- some drawbacks, it goes splendidly uphill, doesn't it, Brown?"

"That is its strong point," I answered, grateful for the unexpected and kindly word of recognition thrown to me, one of the Others; but the Frenchman did not deign to notice the chauffeur.

"Capital!" cried he. "If mademoiselle be willing, and a hill can be found in the neighbourhood, I should like to wager my Pieper against her seven-horse-power German car. I had an odd experience the other day," he went on. "My motor stopped for want of essence; luckily it was in a village, but there wasn't a drop of essence to be bought - all the shops were sold out. What do you think I did, mademoiselle? I filled the tank with absinthe from a café, and got home on that. Not many would have thought of it, eh?"

"Few indeed," said I to myself, for it was news to me that his carburetter could burn heavy oil. While I was reflecting that automobiling, like fishing, is a pursuit whose followers are peculiarly ready to sacrifice truth on the altar of picturesqueness, luncheon was over, and we all rose. With what seemed to me detestable impertinence, though clearly not understood as such by innocent Miss Randolph, the Frenchman sauntered by the side of the ladies as if to go with them to the Château. Perhaps my young mistress was touched by the look of gloom that doubtless clouded my insignificant features, for she promptly and cordially tendered me an invitation to go with them. "You know, Brown," she said, "we look on you as our guide as well as our chauffeur" ("and I must be your watch-dog too, though it isn't in the contract," I grumbled to myself, "if you are going to allow every automobilist who claims the right of fellowship to thrust himself upon you").

Even Aunt Mary was impressed as we passed into the inner court of Chambord, and Miss Randolph (whose sympathy and imagination throws her at once into harmony with her surroundings) drew a quick breath of half-awed astonishment at sight of this enormous structure, more like a city than a single house, with its prodigious towers, its extraordinary assemblage of pinnacles, gables, turrets, cones, chimneys and gargoyles. The Frenchman minced along at her side, twirling his moustache, and making great play with those long-lashed eyes of his. I divined his intention to outdistance us, and get Miss Randolph to himself in the labyrinth of vast, empty rooms through which our party was paraded by a languid guide; but thwarted him by hastening Aunt Mary's steps and keeping upon their heels in my new character of watch-dog. I was more annoyed than I care to tell you when I saw that she seemed to like his idiotic compliments; but when I heard him tell her airily that Chambord was built by Louis the Fourteenth, and Miss Randolph turned questioningly to me with a puzzled little wrinkle on her forehead, I felt that my time had come.

I began something reprehensively like a lecture on Chambord, putting myself by Miss Randolph's side, and determined that the Frenchman should get no further chance. I pointed out the constant recurrence of the salamander, the emblem of Francis the First, the builder of the house, and I told how he had selected this sandy waste to build it on, because the Comtesse de Thoury had once lived near by, she having been one of the earliest loves of that oft-loving King. I enlarged upon the characteristics of French Renaissance architecture, pointed out the unity in variety of the design of Pierre Nepveu, the obscure but splendid genius who planned the house as something between a fortified castle and an Italian palace; showed them the H entwined with a crescent on those parts of the house that were built by Henry the Second; and sketched the history of the place, talking about Marshal Saxe, Stanislas of Poland, the Revolution of 1792, and the subsequent tenancy of Berthier. I can tell you that when once I was started, the absinthe-driver was bowled over. I simply sprawled all over Chambord, talked for once as well as I knew how, directed all my remarks to Miss Randolph, who - "though I say it as shouldn't" - seemed dazzled by my fireworks. An English girl must have been struck with the incongruity of a hired mechanic spouting French history like a public lecturer, but she, I think, only put it down to some difference in the standard of English education. Anyhow, the Frenchman was done for, and Miss Randolph and I plunged into an interesting talk, shunting the new acquaintance upon Aunt Mary. As she can speak no French and he no English, they must have had a "Jack-Sprat-and-his-wife" experience.

For that happy hour while we wandered through the echoing-rooms of Chambord, climbed the wonderful double staircase, and walked about the intricate roof, I was no longer James Brown, the hired mechanic, but John Winston, private gentleman and man at large, with a taste for travel. There came a horrid wrench when I had to remember that I had chosen to make myself one of the unclassed, one of the "others." The autumnal twilight was falling; we had to get to Blois on a car that might commit any atrocity at any instant. Yet, strange to say, it had a magnanimous impulse, started easily, and ran smoothly. The somewhat subdued Frenchman started just before us on his little Pieper, and soon outpaced our solid chariot. We went back to St. Dié, took the road by the Loire, and as dusk was falling crossed the camel-backed bridge over the great river, and went up the Rue Denis Pépin into the ancient city of Blois. The Château does not show its best face to the riverside, being hemmed in by other buildings, so I drove past our hotel and on to the pretty green place where the great many-windowed Château springs aloft from its huge foundation. "The famous Château of Blois," I remarked, waving a hand towards it. "The old home of the kings of France." We all sat and looked up at the huge, silent building, the glowing colours of its recessed windows catching the last beams of departing day.

"I suppose its only tenants now are ghosts," said Miss Randolph. "I can imagine that I see wicked Catherine de Medicis glaring at us from that high window near the tower." It was an impressive introduction to one of the greatest monuments of France, and after we had gazed a little longer I turned the car and drove back into the courtyard of the Grand Hotel de Blois, where tame partridges pecked at grain upon the ground, many dogs gambolled, and foreign birds bickered and chattered in huge cages. At the entrance was the Frenchman, all eyes and eyelashes, darting forward to help Miss Randolph from her car.

I grew weary to nausea of this shallow, pretentious ass, with no knowledge of his own land. It began to shape itself in my mind that though a gentleman in exterior he was the common or garden fortune-hunter, or perhaps worse. Finding a beautiful American girl travelling en automobile, chaperoned only by a rather foolish and pliable aunt, he fancied her an easy prey to his elaborate manners and eyelashes. Knowing we were coming to the "Grand," I had directed Almond to drive the Napier to the "France," and my duty for the day being over, I was about to go across to change and dine, when I saw Miss Randolph in the hall. She was annoyed, she told me, to find that the best suite of rooms were taken by some rich Englishman and his daughter, and she had to put up with second-rate ones. "Poor Monsieur Talleyrand," she ended, "has little more than a cupboard to sleep in." Talleyrand, then, was the name of the Frenchman. "Oh, is he stopping here?" I asked. "He said he was going on at once to Biarritz."

"He's changed his mind," said she. "He's so impressed with Chambord that he says it's a pity not to see all the other châteaux, which are so important in the history of his own country. He asked Aunt Mary if we should mind his going at the same time with us. So of course she said we wouldn't." All this, if you please, with the most candid air of guilelessness, which I actually believe was genuine.

"She said what?" I demanded, quite forgetting my part in my rage.

"She said," repeated Miss Randolph slowly and with dignity, "that we would not mind his seeing the châteaux when we see them. Why should we mind? The poor young man won't do us any harm, and it's quite right of him to want to see his own castles, because, anyhow, they're a great deal more his than ours."

I was still out of myself, or rather out of Brown.

"But is it possible, my dear Miss Randolph," I was mad enough to exclaim (I, who had never before risen above the level of a humble "miss"), "that you and Miss Kedison believe in that flimsy excuse? The castles--"

"Yes, the castles" she repeated, very properly taking the word out of my mouth; and the worst of it was that she was completely right in setting me in my place, setting me down hard. "I am surprised at you, Brown. You are a splendid mechanic, and-and you have travelled and read such a lot that you are a very good guide too, and because I think we're lucky to have got you I treat you quite differently from an ordinary chauffeur" (If you could have heard that "ordinary" as she said it! There was hope in it in the midst of humiliation; but I dared not let a gleam dart from my respectful eye.) "Still, you must remember, please, that you are engaged for certain things and not for others. If I need a protector besides Aunt Mary, I may tell you.

I could have burst into unholy laughter to hear the poor child; but I bottled it up, and only ventured to say, with a kind of soapy meekness which I hoped might lather over the real presumption, "I beg your pardon, miss, and I hope you won't be offended; but, as you say, I have travelled a little, and I know something of Frenchmen. They don't always understand American young ladies as well as--"

"'As well as Englishmen,' I suppose you were going to say," snapped she, that dimpled chin of hers suddenly seeming to assume a national squareness I'd never observed. "But Monsieur Talleyrand, though a Frenchman, is a gentleman."

That's what I had to swallow, my boy. The inference was that a French gentleman was, at worst, a cut above an English mechanic, and with that she turned her back on me and ran upstairs with such a rustling of unseen silk things as made me feel her very petticoats were bristling with indignation.

I could have shaken the girl. And the things I said to myself as I stalked over to my own hotel won't bear repeating; they might set the mail-bag an fire; combustibles aren't allowed in the post, I believe. I swore that (among other things) one such snubbing was enough. If Miss Randolph wanted to get herself in the devil of a scrape, she could do it, but I wasn't going to stand by and look complacently on while that smirking Beast made fools of her and her aunt. I'd clear out to-morrow; didn't care a hang whether she found out the trick I'd played or not.

That mood lasted about ten minutes, then I began to realise that, talking of beasts, there was something of the sort inside my own leather coat, and that if anyone deserved a shaking, it was Jack Winston, and not that poor, pretty little thing. I was bound to stop on in the place and protect her, whether she knew she wanted any protection except Aunt Mary's (oh, Lord!) or not. Besides, I wanted the place, since it was the best I could expect for the present, and where Talleyrand (?) was, there would I be also, so long as he was near Her.

Bath and dinner brought me once more as near to an angelic disposition as I hope to attain in this sphere; and, while I was supposed to be earning my screw by cleaning the loathsome car, and making new fastenings for spare belts, I was complacently watching poor Almond in the throes of these Herculean labours. N.B.- It's only fair to myself to tell you that Almond is getting double wages, and is quite satisfied, though I'm persuaded he thinks he has a madman for a master.

About half-past nine next morning (that's yesterday, in case you're getting mixed) I was hanging round the German chariot with a duster, pretending to flick specks off it, though Almond had left none, when Miss Randolph, Aunt Mary, and the alleged Talleyrand came out of the coffee-room, laughing and talking like the best of friends. Talleyrand was now in ordinary clothes, perhaps to point the difference between himself and a mere professional chauffeur. Miss Randolph looked adorable. She'd put off her motoring get-up, and was no end of a swell. This I saw without seeming to see, for we had not met since our scene. I didn't know where I stood with her, but thought it prudent meanwhile to wear a humble air of conscious rectitude, misunderstood.

Talleyrand was swaggering along without a glance at the chauffeur (why not, indeed?) when Miss Randolph hung back, looked round, and then stopped. "Oh, Brown, do you know as much about the Château of Blois as you did about Chambord?" asked she, in a voice as sweet as the Lost Chord.

"Yes, miss, I think I do," said I, lifting my black leather cap.

"Then, are you too busy to come with us?"

"No, miss, not at all, if I can be of any service."

"But, you know, you needn't come unless you like. Maybe it bores you to be a guide."

Now, if I'd been a gentleman and not a chauffeur, perhaps I should have had a right to suspect just a morsel of innocent, kittenish coquetry in this. As it is with me - and with her - if there's anything of the sort, it's wholly unconscious. But it's the most adorable type of girl who flirts a little with everything human - man, woman, or child - and doesn't know it. I take no flattering unction to myself as Brown. Nevertheless I dutifully responded that it gave me pleasure to make use of such small knowledge as I possessed, and was grateful to her for not hearing Talleyrand murmur that he'd provided himself with the Guide Joanne. After that I could afford to be moderately complacent, even though I had to walk in the rear of the party, and no one took notice of me until I was wanted.

That time came, when we'd wound round the path under the commanding old Château, with its long lines of windows, and reached the exquisite Gothic doorway. From that moment it was the Chambord business over again; and I thanked my foresight for having stopped out of my bed half the night, fagging up all the historical details I'd forgotten. These I brought out with a naturalistic air of having been brought up on them since earliest infancy.

Miss Randolph chatters pretty American French, but doesn't understand as much as she speaks when it's reeled off by the yard, so to say; therefore my explanations in English were more profitable than the French of the official guide, who fell into the background. My delightful American maiden has never travelled abroad before, and she brings with her a fresh eagerness for all the old things that are so new to her. It is a constant joy even for poor handicapped Brown to go about with her, finding how invariably she seizes on the right thing, which she knows by instinct rather than cultivation - though she's evidently what she would call a "college girl."

I halted my little party before the Louis the Twelfth gateway, made them admire the equestrian statue of the good King, drew their attention to the beautiful chimneys and the adornments of the roof, with the agreeable porcupine of Louis, the mild ermine and the constantly recurring festooned rope of that important lady, Anne of Brittany. Then I led them inside, rejoicing in Talleyrand's air of resentful remoteness from my guidance. I scored, too, in his superficial knowledge of English. In the midst of my ciceronage, however, I thought of you, and how we had discussed plans of this trip together. You had looked forward particularly to the Château; and as you've urged me to paint for you what you can't see (this time), your blood be on your own head if I bore you.

You would be happy in the courtyard of the Château, for it would be to your mind, as to mine, one of the most delightful things in Europe. It's a sort of object lesson in French architecture and history, showing at least three periods; and when Miss Randolph looked up at that perfect, open staircase, bewildering in its carved, fantastic beauty, I wasn't surprised to have her ask if she were dreaming it, or if we saw it too. "It's lace, stone lace," she said. And so it is. She coined new adjectives for the windows, the sculptured cornices, the exquisite and ingenious perfection of the incomparable façade.

"I could be so good if I always had this staircase to look at!" she exclaimed. "It didn't seem to have any effect on Catherine de Medici's soul; but then I suppose when she lived here she stopped indoors most of the time, making up poisons. I'm sorry I said yesterday that Francis the First had a ridiculous nose. A man who could build this had a right to have anything he liked, or do anything he liked."

And you should have seen her stare when Talleyrand bestowed an enthusiastic "Comme c'est beau!" on the left wing of the courtyard, for which Gaston d'Orleans' bad taste and foolish extravagance is responsible - a thing not to be named with the joyous Renaissance façade of Francis.

When Miss Randolph could be torn away, we went inside, and throwing off self-consciousness in the good cause, I flung myself into the drama of the Guise murder. Little did I know what I was letting myself in for. My one desire was to interest Miss Randolph, and (incidentally, perhaps) show her what a clever chap she had got for a chauffeur - though he wasn't a gentleman, and Talleyrand was.

I pointed from a window to the spot where stands the house from which the Duc de Guise was decoyed from the arms of his mistress; showed where he stood impatiently leaning against the tall mantelpiece, waiting his audience with Henri the Third; pointed to the threshold of the Vieux Cabinet where he was stabbed in the back as he lifted the arras; told how he ran, crying "a moi!" and where he fell at last to die, bleeding from more than forty wounds, given by the Forty Gentlemen of the Plot; showed the little oratory in which, while the murderous work went on, two monks gabbled prayers for its successful issue.

I got quite interested in my own harangue, inspired by those stars Miss Randolph has for eyes, and didn't notice that my audience had increased, until, at this point, I suddenly heard a shocked echo of Aunt Mary's "Oh!" of horror, murmured in a strange voice, close to my shoulder. Then I looked round and saw a man and a girl, who were evidently hanging on my words.

The man was the type one sees on advertisements of succulent sauces; you know, the smiling, full-bodied, red-faced, good-natured John Bull sort, who is depicted smacking his lips over a meal accompanied by The Sauce, which has produced the ecstasy. One glance at his shaven upper lip, his chin beard, and his keen but kindly eye, and I set him down as a comfortable manufacturer on a holiday - a Lancashire or Yorkshire man. The girl might be a daughter or young wife; I thought the former. A handsome creature, with big black eyes and a luscious, peach-like colour; style of hairdressing conscientiously copied from Queen Alexandra's; fine figure, well shown off by a too elaborate dress probably bought at the wrong shop in Paris; you felt she had been sent by doting parents to a boarding-school for "the daughters of noblemen and gentlemen"; no expense spared.

It was she who had echoed Aunt Mary; and when I turned she bridled. Yes, I think that's the only word for what she did. But it was the man who spoke.

"I beg your pardon," he said, dividing the apology among the whole party, and taking off his unspeakably solid hat to the ladies. "I hope there's no objection to me and my daughter listening to this very intelligent guide? She's learned French, but it doesn't seem to work here; she thinks it's too Parisian for Blois, but anyhow, we couldn't either of us understand a word the French guide said, so we took the liberty of joining on to you, with a great deal of pleasure and profit."

He had a sort of engaging ingenuousness, mixed with shrewdness of the provincial order, and I could see that he appealed to my American girl, though I don't think she cottoned to the daughter. She smiled at the papa, as if for the sake of her own; and in a few pretty words practically made him a present of me, that is, she offered to let him share me for the rest of the tour round the Château. I was not sorry, as I hoped that the daughter might occupy the attention of Monsieur Talleyrand; and as, under these new conditions, we continued our explorations, I adroitly contrived to divide off the party as follows: Miss Randolph, the Lancashire man (his accent had placed him in my mind), and myself; Aunt Mary, the new girl, and our gentleman of the eyelashes. This arrangement was satisfactory to me and the old man, whether it was to anybody else or not; and so grouped, we went through the apartments of Catherine de Medicis (Aunt Mary pronounced "those little poison cupboards of hers vurry cunning; so cute of her to keep changing them around all the time!"), and out on the splendid balconies.

The Lancashire man, thanks to Miss Randolph's permission, made himself quite at home with me, bombarding me with historical questions. But it was evident that he was puzzled as to my status.

"You are a first-rate lecturer," said he. "I suppose that's your profession?"

"Not entirely," said I, with a glance at Miss Randolph; but she was enjoying the joke, and not minded to enlighten him. Probably he supposed that leather jacket and leggings was the regulation costume of a lecturing guide

"Do you engage by the day," he inquired, "or by the tour?"

"So far, I have engaged by the tour, sir," I returned, playing up for the amusement of my lady.

He scratched his chin reflectively. "Baedeker recommends several of these old castles in this part of the country," said he. "Do you know 'em all?"

I answered that I had visited them.

"All as interesting as this?"

"Quite, in different ways."

"Hm! Do you speak French?"

"Fairly," I modestly responded.

"Well, if this young lady hasn't engaged you for too long ahead, I should like to talk to you about going on with us. I didn't think I should care to have a courier, but a chap like you would add a good deal to the pleasure of a trip. Seems to me you are a sort of walking encyclopædia. I would pay you whatever you asked, in reason--"

"And, oh, papa, he might go on with us all the way to Cannes!" chipped in the daughter, which was my first intimation that she was listening. But she had joined the forward group, and the words addressed to Pa were apparently spoken at me. I dared not look at Miss Randolph, but I hoped that a background of other people's approval might set me off well in her eyes.

I was collecting my wits for an adequate answer, when she relieved me of the responsibility. I might even say she snapped up the young lady from Lancashire.

"I'm afraid I must disappoint you," she replied for her chauffeur. "He is engaged to me. I mean" (and she blushed divinely) "he is under engagement to remain with my aunt and myself for some time. We are making a tour on an automobile."

"I beg your pardon, I'm sure," said the old fellow, as the American and the English girl eyed each other - or each other's dresses. "I didn't understand the arrangement. When you are free, though," he went on, turning to me, "you might just let me know. We're thinking of travelling about for some time, and I've taken a liking to your ways. I'm at the 'Grand' here at Blois for the day, then we go on to Tours, and so by easy stages to the Riviera. At Cannes, we shall settle down for a bit, as my daughter has a friend who's expecting us to meet her there. But I'll give you my card, with my home address on it, and a letter, or, better still, a wire, would be forwarded." He then thanked Miss Randolph for me, thanked me for myself, and, with a last flourish of trumpets, handed me his card.

By this time we had "done" the castle, as conscientious Aunt Mary would say, and were parting. All exchanged bows (Miss Randolph's and the Lancashire girl's expressive of armed neutrality) and parted. I thereupon glanced at the card and got a sensation.

"Mr. Jabez Barrow, Edenholme Hall, Liverpool," was what I read. That conveys little to you, though as an address it has suggestive charm, but to me it meant nothing less than a complication. Queer, what a little place the world is! To make clear the situation I need only say, "The Cotton King." Yes, that's it; you've guessed it. These Barrows are my mother's newest protégés. Jabez Barrow is the "quaint, original old man" she is so anxious for me to meet, and, indeed, has made arrangements that I should meet. Miss Barrow is the "beautiful girl with wonderful eyes and such charming ways," who, in my dear mother's opinion, would be so desirable as a daughter-in-law. Had not your doctors knocked our plans on the head you would have had the pleasure of being introduced in my company to the heiress, when I should have made you a present of my chance to add to your own. As it is - well, I don't quite see that any bother can come out of this coincidence, but I must keep a sharp lookout for myself. I saw no Kodak in the hands of the gilded ones, or - by-and-by - my mother might receive a shock. But perhaps they may have possessed and concealed it.

Into the midst of my broodings over the card broke the voice of Miss Randolph, in whose wake I was now following down the picturesque old street to the hotel. Talleyrand was in attendance again, and she had merely to say that the car was to be ready for start to Amboise after luncheon. Accordingly I stepped over to my own private lair, told Almond to get off at once with my Napier to Amboise, putting up at a hotel I named and awaiting instructions.

Have you begun to think there's to be no end to this letter? Well, I shall try to whet your curiosity for what's still to come by saying that I have availed myself of a strange blank interval in the middle of the night for the writing of it, and that dawn can't now be far off. When it breaks this adventure of mine will have reached a crisis - a distinctly new development. But enough of hints.

This country of the Loire is exquisite; it has both grandeur and simple beauty, and the road winding above the river is practically level and in splendid condition; ideal for motors and "hay-motors." The distance between the good town of Blois and Amboise is less than twenty miles. Any decent-minded motor would whistle along from the great grey Château to the brilliant cream-white one under the hour, but that isn't the way of our Demon.

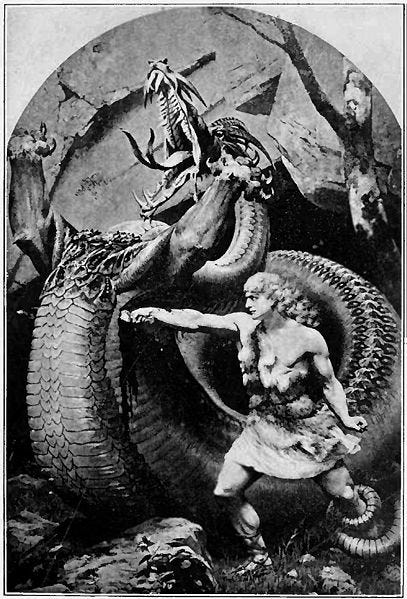

Miss Randolph once said that owning a motor-car was like having a half-tamed dragon in the family. She is quite right about her motor-car, poor child! The Demon had been behaving somewhat less fiendishly of late, and I had hopes of a successful run to Amboise, which I particularly desired, as Eyelashes was to accompany us with his Pieper. But this good conduct had been no more than a trick.

The luggage was loaded up; Talleyrand was making himself officious about helping the ladies, who were in the courtyard ready to mount, when the motor took it into its vile head not to start - a little attack of faintness, owing to the petrol being cold perhaps. Of course, there was the usual crowd of hotel servants and loafers to see us off, and beyond, standing as interested spectators on the steps, who but Jabez Barrow and his handsome daughter.

I tell you the perspiration decorated my forehead in beads when I'd made a dozen fruitless efforts to start that family dragon, Eyelashes maddening me the while with a series of idiotic suggestions. Even Miss Randolph began to get a little nervous, and called out to me, "What can be the matter, Brown? I thought you were such a strong man too. Do let Monsieur Talleyrand try, as he's an expert."

I could see Eyelashes didn't like that suggestion a little bit, consequently I welcomed it. It's very well to dance about and give advice, quite another thing to do the work yourself; but I gleefully stood aside while he grasped the starting-handle. It takes both strength and knack to start that car, and he had neither. At first he couldn't get the handle round against the compression; then, exerting himself further, there came a terrific back-fire - the handle flew round, knocked him off his feet, and sent him staggering, very pale, into the arms of a white-aproned waiter. I couldn't help grinning, and I fancy Miss Randolph hid a smile behind her handkerchief.

Eyelashes was furious. "It is a horror, that German machine!" he cried. "Such a thing has no right to exist. Look at mine!" He darted to his Pieper, gave one twist of the handle, and the motor instantly leaped into life. Everyone murmured approval at this demonstration of the superiority of France, or rather, Belgium, to Germany; but next moment I had got our motor to start. The ladies dubiously took their places, and under the critical dark eyes of Miss Barrow I steered out into the streets of Blois.

I will spare you the detailed horrors of the next few hours. It seemed to me that to keep that car going one must have the agility of a monkey, the strength of a Sandow, and the resourcefulness of a Sherlock Holmes. Almost everything went wrong that could go wrong. Both chains snapped - that was trifling except for the waste of time, but finally the exhaust-valve spring broke. It was getting dusk by this time, and to replace that spring was one of the grisliest of my automobile experiences. To get at it I had to lift off all the upper body of the car and take out both the inlet and the exhaust valves. As darkness came on, Miss Randolph (who took it all splendidly and laughed at our misfortunes) held a lamp while I wrestled with the spring and valves. The Frenchman, who had kept close to us on his irritatingly perfect little Pieper, I simply used as a labourer, ordering him about as I pleased - my one satisfaction. After an hour's work (much of the time on my back under the car, with green oil dripping into my hair!) I got the new spring on, and we could start again. Then - horror on horror's head! - we had not gone two miles before I heard a strange clack! clack! and looking behind, saw that one of the back tyres was loose, hanging to the wheel in a kind of festoon, like a fat worm.

It was eight o'clock; we had lunched at one; the night was dark; we were still miles short of Amboise; if the tyre came right off, it would be awkward to run on the rim. I explained this, suggesting that we should leave the car for a night at a farmhouse, which presumably existed behind a high, glimmering white wall near which we happened to halt, and try to get a conveyance of some sort to drive on to Amboise.

But I had calculated without Eyelashes. Instantly he saw his chance, and seized it. Figuratively he laid his Pieper at the ladies' feet. To be sure, it was built for only two, but the seat was very wide; there was plenty of room; he would be only too glad to whirl them off to the most comfortable hotel at Amboise, which could be reached in no time. As for the chauffeur, he could be left to look after the car.

The chauffeur, however, did not see this in the same light. Not that he minded the slight hardship, if any, but to see his liege lady whisked off from under his eyes by the villain of the piece was too much.

Think how you would have felt in my place. But the hideous part was that, like "A" in a "Vanity Fair" Hard Case, I could do nothing. The proposal was vexatiously sensible, and I had to stand swallowing my objections while Miss Randolph and her aunt decided.

I saw her move a step or two towards the Pieper silently, rather gloomily, but Aunt Mary was grimly alert. Eyelashes had, I had learned through snatches of conversation on board the car, been tactful enough to present Aunt Mary with a little brooch and a couple of hat-pins of the charming faïence made by a famous man in Blois. Intrinsically of no great value, they rejoiced in ermine and porcupine crests, with exquisitely coloured backgrounds, and the guileless lady's heart had been completely won. She now emphatically voted for the Frenchman and his car. But I have already noted a little peculiarity of Miss Randolph's, which I have also observed in other delightful girls, though none as delightful as she. If she is undecided about a thing, and somebody else takes it for granted she is going to do it, she is immediately certain that she never contemplated anything of the kind.

This welcome idiosyncrasy now proved my friend. "Why, Aunt Mary," she exclaimed, "you wouldn't have me go off and desert my own car, in the middle of the night too? I couldn't think of such a thing. You can go with Monsieur Talleyrand, if you want to, but I shall stay here till everything is settled."

I was really sorry for Aunt Mary. She was almost ready to cry.

"You know perfectly well I shouldn't dream of leaving you here, perhaps to be murdered," whimpered she. "Where you stay, I stay."

She had the air of an elderly female Casabianca.

As for Miss Randolph, I adored her when she bade me go with her to investigate what lay behind the wall, and told Talleyrand off for sentinel duty over Aunt Mary and the car in the road.

At first sight the wall seemed a blank one, but I found a large gate, pushed it open, and we walked into the darkness of a great farmyard. Not a glimmer showed the position of the house, but a clatter of hoofs and a chink of light guided us towards a stable, where a giant man with aquiline face was rubbing down a rusty and aged horse. He started and fixed a suspicious stare on me, and I daresay that I was a forbidding figure in my dirty leather clothes, with smears of oil upon my face. His expression lightened a little at sight of my companion, but he was inflexible in his refusal to drive us anywhere. His old mare had cast a shoe on her way home just now; he would not take her out again. Could he, then, Miss Randolph asked, give us rooms for the night, and food? As to that he was not sure, but would consult his wife. He tramped before us to the big dark house, put down his lantern in the hall, opened a door, and ushered us into a dark room, following and closing the door behind him. The room was airless and heavy with the odour of cooking. The darkness was intense, and from the midst of it came a strange sound of jabbering and bleating which for the life of me I couldn't understand. I felt Miss Randolph draw near me as if for protection, then with the scratch of a match and a flicker from a lamp which the farmer was lighting, was revealed the cause of the weird sounds. Seated by the stove was a pathetically old woman, with pendulous chin and rheumy eyes. Swinging her palsied head from side to side, she jabbered and bleated incoherently to herself, being abandoned to this plague of darkness doubtless from motives of economy.

The farmer's wife appeared, and after much discussion it was arranged that the ladies could have a double-bedded room, and there was a small one that would do for Monsieur Talleyrand; but the mécanicien would have to sleep in the barn, where he could have some clean straw. Supper could be ready in half an hour, but we were not to expect the luxuries of a hotel.

The farmer and I carried the ladies' hand-luggage upstairs into a mysterious dim region, where all was clean and cold. I had a flickering, candle-lit vision of a big white room, with an enormously high bedstead, bare floor, a rug or two, a chair or two, a shrine, and a washhand-stand with a knitted cover, one basin the size of a porridge-bowl containing a thing like a milk-jug. Then I set down my burden and departed to wheel the great helpless car into the farmyard, and wash my hands with Hudson's soap in a trough under a pump outside the kitchen.

Meanwhile preparations for supper went on, and as I was hungrily hoping for scraps when my betters should have finished, who should pop out but that Angel to say that supper was ready, and would I eat with them! I had been working so hard and must be starved. If she had guessed how I longed to kiss her she would have run away indoors much faster than she did.

There was soup, chicken, an omelette, and cheese. Trust a Frenchwoman - even the humblest - to turn out an excellent meal on the shortest notice. Miss Randolph smiled and beamed on them, so that in five minutes the farmer and his wife were her willing slaves. She was delighted with the "adventure," as she called it, declaring that the whole thing would be the greatest fun in the world. She was glad that the horrid tyre had come off, as it gave her the chance, which she would never have had otherwise, of studying French peasant life at first hand. Aunt Mary was called in from outside and acquiesced, as she always did, in the arrangements made by her impetuous niece; the farmer and I had pushed the German car inside the gate and left it; but Talleyrand was fussy about getting proper cover for his smart Pieper, and was not satisfied until he had housed it in a dry barn near the house.

After supper I strolled out into the night, trying, with a pipe between my lips, to think out the details of an alluring new plan which had flashed into my mind.

"Flashed" there, do I say? Forced, rammed in, and pounded down expresses it better. Will you believe it, during supper, that fellow - Eyelashes, I mean - had had the audacity to urge upon Miss Randolph that she must now continue the tour on his car!

I was smoking and fuming in the dark, in a corner down by the gateway, when I heard a whisper of silk (I suppose it's linings; I'd know it at the North Pole as hers, now), and detected a shadow which I knew meant Miss Randolph. She came nearer. I saw her distinctly now, for she was carrying a lantern. At first I thought she was looking for me, but she wasn't. She went straight to the car and stood glowering at it for a minute, having set down the lantern. Then she took Something out of the folds of her dress and seemed to feel it with her hand. "Oh, you won't go, won't you?" she inquired sardonically. "You like to break your belts and go dropping your chains about, just to give Brown all the trouble you can, don't you, and keep us from getting anywhere? You think it's enough to be beautiful, and you can be as much of a beast as you like. But you're not beautiful. You're horrid, and I hate you! Take that!"

Up went the Something in her hand; it glittered in the yellow light of the lantern. If you will believe it, the girl had got a hatchet and was chopping at the car. Her poor vicious little stroke did no great damage, but she chipped off a big flake of varnish and left a white gash.

"Oh!" she exclaimed, as if it had hurt her and not her great lumbering dragon. "Oh, you deserve it, you know, and a lot more. But- but--" and she gave a little gurgling sigh.

I had been on the point of bursting out with uncontrollable laughter, but suddenly I ceased to find the thing funny. I couldn't lurk in ambush and hear any more; I couldn't sneak away - even to spare her feelings - and leave her there to cry, for I felt she was going to cry. So I came out into the circle of lantern-light, shaking the tobacco from my pipe.

"Why, Brown, is that you?" she quavered. "I- I didn't want anyone to see me, and I wasn't crying about the car, but just Because- because of everything. I found that hatchet, and- I couldn't help it. I'm sorry now, though. It was mean of me to hit a thing when it's down, even if it is a Beast. It does deserve to be killed, though. It's simply no use trying to go on with such a thing- is it?"

Because of the Plan in my mind I replied gloomily that the prospect was rather discouraging.

"Discouraging! It's impossible!" she cried. "I've been hoping against hope, but I see that now. I won't ask poppa to buy me another; it's too ridiculous. So there's nothing left except to go on by train everywhere, unless- you heard how kind Monsieur Talleyrand was about offering to take us on his car."

In the lantern light I thought I saw that she was beginning to look enigmatic, but I couldn't trust my eyes at this moment. There were a good many stars floating before them - not heavenly - the kind I should have liked to make Talleyrand see.

"Yes, miss, I heard," I said brutally, "and, of course, if you and your aunt would like that, I could wire to Mr. Barrow, the gentleman who went round the Château with us to-day, that I was free to take an engagement with him and his daughter."

She turned on me like a flash. "Oh, is that what you are thinking of? Well- certainly you may consider yourself free- perfectly free. You are under no contract. Go! go to-morrow- or even to-night if you wish. Leave me here with my car. I can go back to Paris, or- or somewhere."

"But I thought you were going on with the French gentleman?" I said.

"I should not think of going with him," she announced icily.

"You said--"

"I said he invited me. I never said I meant to go; I couldn't have said it. For I should hate going with him. There would be no fun in that at all. I want my own car or none. But that need not matter to you. Go with your Barrows.

"Begging your pardon, miss, I don't want to go with any Barrows."

"But you said--"

"If you wished to get rid of me--"

"I wish 'to get rid of' you! I don't repudiate my- business arrangements in that way."

"May I stop on with you, then, miss?" I pleaded at my meekest. "I'll try and do the best I can about the car."

"Oh, do you really think there's any hope?" She clasped her hands and looked at me as if I were an oracle. Her eyelashes are very long. I wonder why they are so charming on her and so abominable on a Frenchman?

"I've got an idea in my mind, miss," said I, "that might make everything all right."

"Brown," said she, "you are a kind of leather angel."

Then we both laughed. And I am afraid it occurred to her that the ground we were touching was not calculated to bear a lady and her mécanicien, for she turned and ran away.

It was not yet ten o'clock, and I had something better to do than crawl into the bed of straw that had been offered me. It was not much more than ten miles to Amboise, and opening the great gate as quietly as I could, I stepped out upon the white road and set off briskly for the town, my Plan guiding me like a big bright beacon.

What I meant to do - what I was meaning and wanting at this present moment to do - is this.

Being now at Amboise, having knocked up the hotel porter on arriving, I shall let poor old Almond sleep the sleep of the just until the earliest crack of dawn. Then I shall wake him, have my Napier got ready - if that hasn't been done overnight - pay him, press an extra tip into his not unwilling palm, pack him off to England, home, and beauty, after which I shall romp back to the sleeping farmhouse on my own good car.

My story to Miss Randolph will be that while in Blois yesterday I heard from my master. He is called back to England in a great hurry, wants to leave his car, and would be delighted to let it out on hire at reasonable terms if driven by a good, responsible man - like me. I suppose I shall have to name a sum - say a louis a day - or she'll suspect some game.

She is sure to snatch at a chance, as a drowning man at a straw, and I pat myself on the back for my inspiration. I am looking forward to a new lease of life with the Napier.

The window grows grey; I must call Almond. How the Plan works out you shall hear in my next. Au revoir, then.

Your more than ever excited friend,

Jack Winston.

MOLLY RANDOLPH TO HER FATHER

Amboise,

November Something-or-Other.

Dear old Lamb,

Did you know that you were the papa of a chameleon? An eccentric combination. But Aunt Mary says she has found out that I am one - a chameleon, I mean; but I don't doubt she thinks me an "eccentric combination" too. And, anyway, I don't see how I can help being changeable. Circumstances and motor-cars rule dispositions.

I wrote you a long letter from Blois, but little did I think then - no, that isn't the way to begin. I believe my starting-handle must have gone wrong, to say nothing of my valves - I mean nerves.

Last night we broke down at the other end of nowhere, and rather than desert Mr. Micawber, alias the automobile, I decided to stop till next morning at a wayside farmhouse - the sort of place, as Aunt Mary said, "where anything might happen."

Of course, I needn't have stayed. The Frenchman I told you about in my last letter offered to take us and some of our luggage on to Amboise on his little car; but I didn't feel like saying "yes" to that proposal, and I was sorry for poor Brown, who had worked like a Trojan. Besides, to stay was an adventure. Monsieur Talleyrand stopped too, and we had quite a nice supper in a big farm kitchen, but not as big as the room which the people gave Aunt Mary and me - a very decent room, with two funny high beds in it. I couldn't sleep much, because of remorse about something I had done. I'm ashamed to tell you what, but you needn't worry, for it only concerns the car. And then I didn't know in the least how we were to get on again next day, as this time the automobile had taken measures to secure itself a good long rest.

I'd dropped off to sleep after several hours of staring into the dark and wondering if Brown by some inspiration would get us out of our scrape, when a hand, trying to find my face, woke me up. "It's come!" I thought. "They're going to murder us." And I was just on the point of shrieking with all my might to Brown to save me, when I realized that the hand was Aunt Mary's; it was Aunt Mary's voice also saying, in a sharp whisper, "What's that? What's that?"

"That," I soon discovered, was a curious sound which I suppose had roused Aunt Mary, and sent her bounding out of bed, like a baseball, in her old age. I forgot to tell you that in one corner of our room, behind a calico curtain, was a queer, low green door, which we had wondered at and tried to open, but found locked. Now the sound was coming from behind that door. It was a scuffling and stumbling of feet, and a creepy, snorting noise.

Even I was frightened, but it wouldn't do, on account of discipline, to let Aunt Mary guess. I just sort of formed a hollow square, told myself that my country expected me to do my duty, jumped up, found matches, lighted our one candle, and with it the lamp of my own courage. That burned so brightly, I had presence of mind to take the key out of the other door and try it in the mysterious green lock. It didn't fit, but it opened the door; and what do you think was on the other side? Why, a ladder-like stairway, leading down into darkness. But it was only the darkness of the family stable, and instead of beholding our landlord and landlady digging a grave for us in a business-like manner, as Aunt Mary fully expected, we saw two cows and a horse, and three of those silly, surprised-looking French chickens which are always running across roads under our automobile's nose.

This was distinctly a relief. We locked the door, and laid ourselves down to sleep once more. But - for me - that was easier said than done. I lay staring into blackness, thinking of many things, until the blackness seemed to grow faintly pale, the way old Mammy Luke's face used to turn ashy when she was frightened at her own slave stories, which she was telling me. The two windows took form, like grey ghosts floating in the dark, and I knew dawn must be coming; but as I watched the squares growing more distinct, so that I was sure I saw and didn't imagine them, a light sprang up. It wasn't the dawn-light, but something vivid and sudden. I was bewildered, for I'd been in a dozy mood. I flew up, all dazed and stupid, to patter across the cold, painted floor on my poor little bare feet.

Our room overlooked the courtyard, and there, almost opposite the window where I stood, a great column of intense yellow flame was rising like a fountain of fire - straight as a poplar, and almost as high. I never saw anything so strange, and I could hardly believe that it wasn't a dream, until a voice seemed to say inside of me, "Why, it's your car that's on fire!"

In half a second I was sure the voice was right, and at once I was quite calm. How the car could have got on fire of its own accord was a mystery, unless it had spontaneous combustion, like that awful old man of Dickens, who burnt up and left a greasy black smudge; but there was no time to think, and I only kept saying to myself, as I hurried to slip on a few clothes (the sketchiest toilet I ever made, just a mere outline), how lucky it was that my automobile stood in the courtyard where there was no roof, instead of being in the barn, like Monsieur Talleyrand's. And I knew that Brown slept in the barn, so that, if it had happened there, he might have been burnt to death in his sleep, which made me feel as if I should have to faint away, even to imagine.

But I didn't faint. I tore out of the room, as soon as I was dressed, with my long, fur-lined motoring coat over my "nighty," and yelled "Fire!" at the top of my lungs. But I forgot to yell in French, so of course the farm people couldn't have understood what was the matter, unless they'd seen the light from their windows. It was still dark in the shut-up house, but somehow I found my way downstairs, and to the door by which we'd all come trooping in the evening before. Nobody had appeared yet (though I fancied I heard Aunt Mary's frantic voice), so I concluded that the farmer and his wife must be outside in the fields about their day's work, for these French peasants rise with the dawn, or before it.

I pulled open the door, and the light of the fire struck right at my eyes, which had got used to the darkness in the passage. There was the pillar of fire, as bright and straight and amazingly high as ever, not a trace of the car to be seen in the midst; but silhouetted against the yellow screen of flame was a tall black figure which I recognized as Brown's. He was standing still, looking calmly on, actually with his hands in his pockets, instead of trying to put out the fire, and I was dumbfounded, for always before he had shown himself so resourceful.

I stood still, too, a minute, for I was surprised. Aunt Mary was having hysterics in one of our windows which she'd thrown open; and Monsieur Talleyrand had come close behind me, it seemed, though I didn't know that then.

I heard the queer clucking and roaring of the fire which was drinking gallons of petrol, but the only thing I really thought of was Brown with his hands in his pockets while my car was burning up. I didn't love it - at least I hadn't, and the night before I had behaved to it not at all in a gentlemanly manner, but I couldn't have stood by like that to watch it die without moving a finger.

"Oh, Brown!" I gasped out, running to him, so close that the fire was hot on my face. "Oh, Brown, how can you? Anybody would think that you were glad."

"And he is!" cried a voice in French at my back. "It was he who set your automobile on fire, mademoiselle. I myself, who tell you, saw him do it." I whisked round, and there stood Monsieur Talleyrand, looking very picturesque in an almost theatrical déshabillé, with the firelight shining on him, just as if it were a scene on the stage.

Brown faced round too, and at the same instant, the fire having drunk the last drop of petrol, the flame suddenly died down, and there fell a curious silence after the roaring of the fire, which had been like a blast. The woodwork of the car, the hood and the upper part, as well as the wooden wheels, had all disappeared - the flame had swallowed and digested them. Of my varnished and dignified car there remained only a heap of twisted bits of iron, glowing a dull red. In the grey dawn we must have looked like witches at some secret and unholy rite. The going out of the light had an odd effect upon us three. When Monsieur Talleyrand launched his accusation at Brown, he had thrown up his chin, and the light, striking on his eyeballs, made them glow like red sparks. But with the dying of the light, the flash in his eyes died too; and his face changed to a disagreeable, ashy grey. At the same minute, when I turned to Brown, it was his eyes that glowed, but the light seemed to come from inside.

I forget whether I ever told you that Brown is a very good-looking fellow; too good-looking for a mere chauffeur. His face is like his name - brown; his eyes are brown too, and they can almost speak. One can't help noticing these things, even in one's chauffeur. If he weren't a chauffeur, one might certainly take him for a gentleman. Some things really are a pity! But never mind.

Brown looked at Monsieur Talleyrand, and then he said, "You are a liar." Oh, my goodness, I expected murder!

Monsieur Talleyrand gave a sort of leap.

"Scoundrel, hog, canaille!" he stammered, trembling all over. "To be insulted by an English cad, a common chauffeur, that a gentleman cannot call out, an incendiary--"

But here Brown broke in with a "Silence!" that made me jump. And the funny part was that it was he who looked the gentleman, and Monsieur Talleyrand the cad - quite a little, mean cad, though he is really handsome, with eyelashes you'd have to measure with a tape. That awful "Silence!" seemed to blow his words down his throat like a gust of wind, and while he was getting breath Brown followed up his first shot; but this time it was aimed my way.

"Do you believe what that coward says?" he flung at me, without even taking hold of the words with "Miss" for a handle. Between the two men and the excitement, I gasped instead of answering, and perhaps he took silence for consent, though that is such an old-fashioned theory, especially when it concerns girls. Anyway, he seemed to grow three or four inches taller, and his chin got squarer. "So far from burning your car," said he (and you could have made a block of ice out of each word), "I have been to Amboise to hire a car for you, and thought I had been lucky in securing my old master's.

"As this expedition has occupied the whole night. I have really had no time for plotting, even if there had been a motive, or if I were the sort of man for such work. I hoped you knew I wasn't. But there" - and he pointed to the road outside the open gate - "is my master's car, and the motor is still hot enough to prove--"

"I don't want it to prove," I found breath to exclaim. "Of course, I know you didn't burn my car--"

"But if I say I saw him," cut in Monsieur Talleyrand.

"Pooh!" said I. It was the only word I could think of that went "to the spot," and I hurried on to Brown. "All I minded was seeing you with your hands in your pockets. It didn't seem like you."

"You don't understand," said he. "Just as I opened the doors to drive in the car I'd brought, I saw at a glance that there was something queer about yours. The front seat was off; and as I came nearer I found the screw had been taken out of the petrol tank. With that I caught sight of a flame creeping along a tightly twisted piece of cotton waste - the stuff one cleans cars with. Then I knew that someone had planned to set fire to the car and leave himself time to escape. I sprang at it to knock away the waste, but I was too late. That instant the vapour caught, and I was helpless to do any good, because sand, and a huge lot of it, was the only thing that might have put the fire out, if one could have got it, and then gone near enough to throw it on. Since there was none, the only thing to do was to stand by; and as I'd scorched my hands a little, I suppose I instinctively put them in my pockets."

Monsieur Talleyrand laughed. "You tell your story very well," said he, "but--"

He didn't get farther than that "but," for just then up came running the farmer and his wife from the fields, where they had seen the flames. They began chattering shrilly, in a dreadful state about their buildings, but Brown quieted them down, pointing out that no harm had been done to anything of theirs, and that the fire was out. "Now," he said, "since I didn't burn the car, who did?"

I looked at Monsieur Talleyrand because Brown was looking at him, or rather glaring, when suddenly a loud exclamation from the farmer and his wife made me turn to see what was going to happen next. What I saw was the most wonderful old figure hobbling out of the house, through the door I'd left open - a mere knotted thread of an old thing, in a red flannel nightgown, I think it must have been, and a few streaks of grey hair hanging from a night-cap that tied up its flabby chin. It was the old woman who had breathed so much in the dark the night before; and no wonder they exclaimed at seeing her crawling out of doors, hardly dressed.

Somehow I felt frightened; she was just like a witch - horrifying, but pathetic too, so old, so little life left in her. She would have come hobbling on into the courtyard, but the farmer stopped her; and there she stood on the door-sill, raising herself up and up on her stick, until suddenly she clutched the farmer's arm and pointed the stick straight at Monsieur Talleyrand, gabbling out something which I couldn't understand.

The farmer had just been going to hustle her inside the house, but he changed his mind. "She says you set fire to the automobile," he exclaimed; "she saw it from the window. She thinks you will murder us all. Monsieur, my mother has still her senses. She does not tell foolish lies. You must go out of my house."

"Monstrous!" cried Monsieur Talleyrand. "Am I to be accused on the word of a crazy old witch? I advise you to be careful what you say."

"Here is something else, which speaks for itself," Brown said. "Look!" and he pointed to the ground not far from the gnawed bones of my car. We looked, and saw some wisps of the stuff he had called cotton-waste, twisted up and saturated with oil. "That was used to fire the petrol," he went on. "There was none like it on our car, but you carried plenty in yours. I've seen you use it, and so, I think, has Miss Randolph."

For an instant Talleyrand seemed to be taken aback, and he looked so pale in the dim light that I was almost going to be sorry for him, when with a sudden inspiration he struck an attitude before me. He had the air of ignoring the others, forgetting that they existed.

"Mademoiselle," he said in a low, really beautiful voice, that might have drawn tears from an audience if he had been the leading man cruelly mistaken for a neighbouring villain, "chère mademoiselle, I did what these canaille accuse me of. Yes, I did it! But they cannot understand why. Only you are high enough to understand. It was - because of my great love for you. All is to be forgiven to such love. Cheerfully, a hundred times over, will I pay for this material damage I have done. I am not poor, except in lacking your love. To gain an opportunity of winning it, to take you from your brutal chauffeur, who is not fit to have delicate ladies trusted to his care, I did what I have done, meaning to lay my car, myself, all that I have and am, figuratively at your feet."

If he had really, instead of "figuratively," I'm sure I couldn't have resisted kicking him, which would have been unladylike. How could I ever have thought he was nice? Ugh! I could have strangled him with his own eyelashes! Brown was right about him, after all. I wonder why it doesn't please one more to find out that other people are right?

"I don't want you to pay," said I. "I only want you to go away."